Introduction

Atlantic chub mackerel (Scomber colias) is found throughout the warm and temperate coastal waters in the Atlantic Ocean, as well as the Mediterranean and southern Black Sea (Hernández and Ortega, 2000). It is considered a separate species from the closely related chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus) which is distributed throughout the Pacific Ocean (Catanese et al., 2010). The New England and Mid-Atlantic stock has recently been the target of a commercial fishery that also targets Illex spp., squid, on the eastern coast of the United States. Peak commercial harvest in New England was 239.8 mt for 2014 and 1984.2 mt in the mid-Atlantic for 2013 (NMFS, 2019). Although landings have increased in the US Exclusive Economic Zone (Fig. 1) in recent years, very little is known about the demographic characteristics of the stock. The absence of biological information on S. colias impedes the stock’s assessment and management (Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, 2017).

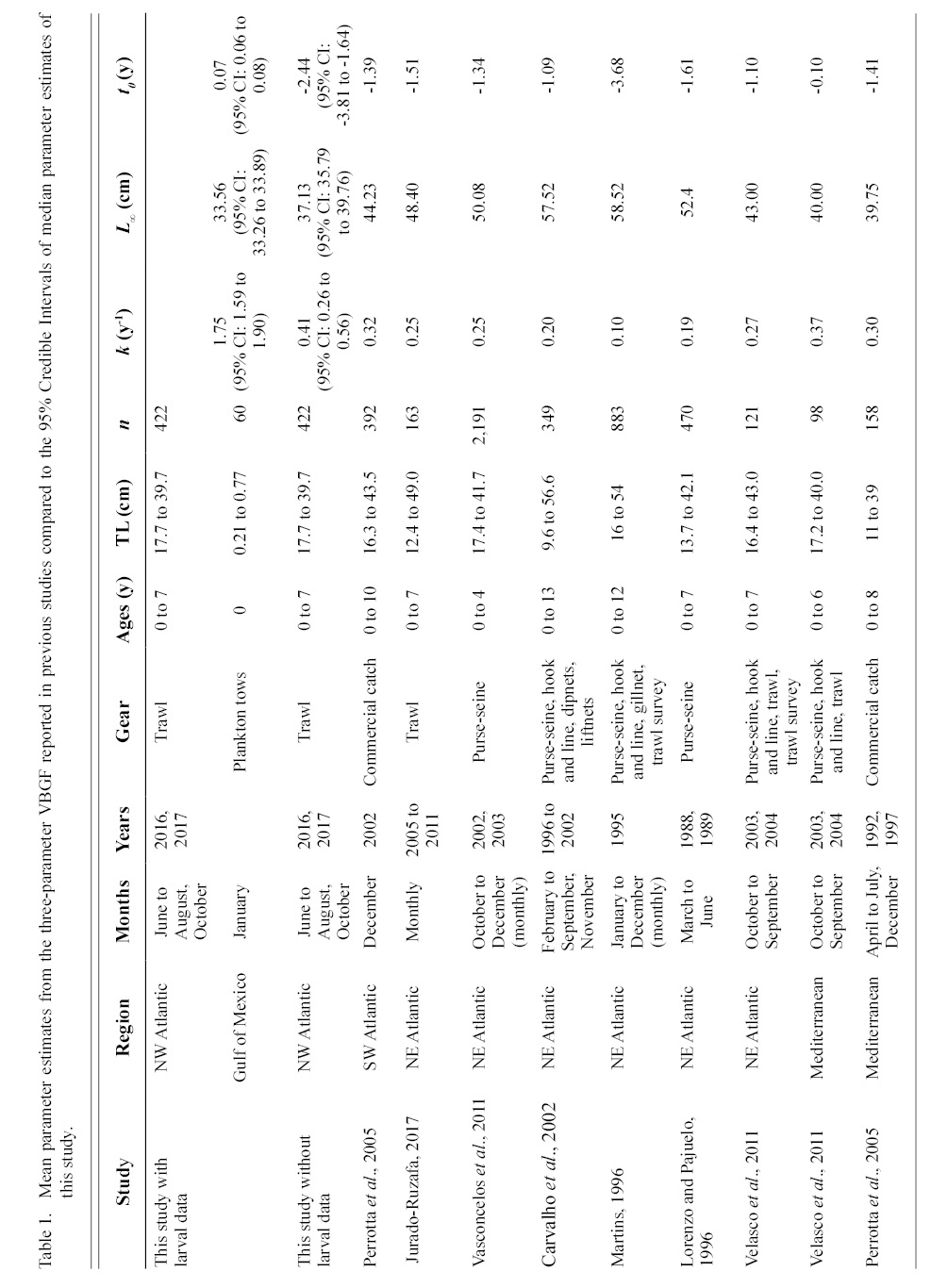

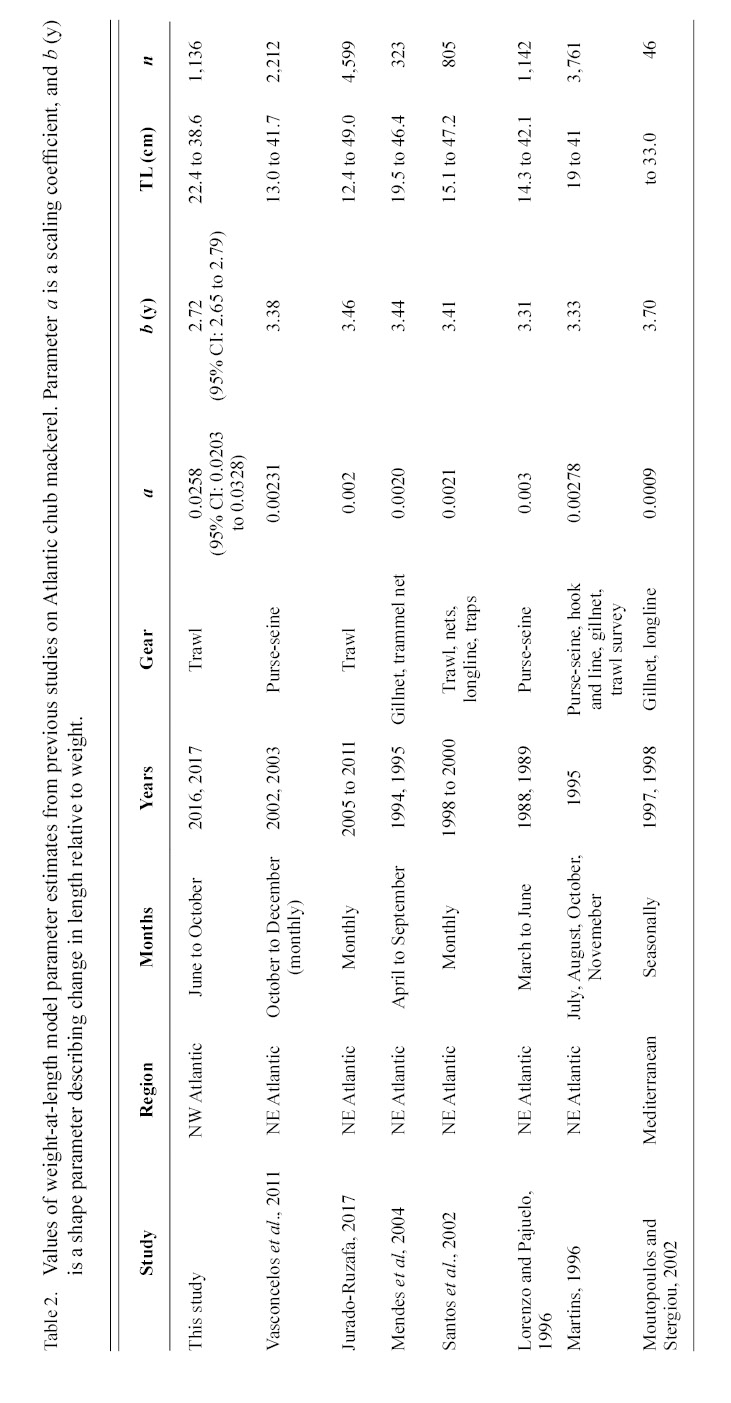

Information on individual growth dynamics is essential for the assessment of exploited stocks (Ballagh et al., 2011). The demographic characteristics of S. colias have been described from populations in the Northeast Atlantic (Martins 1996; Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996; Carvalho et al., 2002; Vasconcelos et al., 2011; Velasco et al., 2011; Jurado-Ruzafa et al., 2017), Mediterranean Sea (Perrotta et al., 2005; Bayhan, 2007; Velasco et al., 2011), and Southwest Atlantic (Perrotta et al., 2005), but have not been described for the stock in the Northwest Atlantic. These studies indicate that considerable geographic variation exists in parameter estimates of Atlantic chub mackerel growth that describe length-at-age (Table 1) and weight-at-length (Table 2) among locations. Given the range of mean parameter estimates, determining whether variations are due to geographic differences in growth or sampling practices is challenging.

Table 1

Contrasts in the growth dynamics of S. colias reported among studies (and regions) can be attributed to several sources, including diversity of gear type used to collect the fish, variations in sample sizes, and temporal variability. Gear type used in commercial harvest varies widely and includes purse-seine (Martins 1996; Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996; Carvalho et al., 2002; Sinovčić et al., 2004; Vasconcelos et al., 2011; Velasco et al., 2011), beach seine (Sinovčić et al., 2004), commercial trawl (Martins 1996; Santos et al., 2002; Velasco et al., 2011; Jurado-Ruzafa et al., 2017), hook and line (Martins 1996; Carvalho et al., 2002; Velasco et al., 2011), longline (Santos et al., 2002; Moutopoulos and Stergiou 2002), traps (Santos et al., 2002), and a variety of other net types (Martins 1996; Carvalho et al., 2002; Santos et al., 2002; Moutopoulos and Stergiou 2002; Mendes et al., 2004). Sample sizes used to describe the length-at-age relationship ranged from 98 (Velasco et al., 2011) to 2 191 individuals (Vasconcelos et al., 2011) and 46 (Moutopoulos and Stergiou 2002) to 4 599 individuals (Jurado-Ruzafa et al., 2017) to describe the weight-at-length relationship. Sample collection also took place during different years and seasons (Martins 1996; Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996; Carvalho et al., 2002; Santos et al., 2002; Moutopoulos and Stergiou, 2002; Sinovčić et al., 2004; Mendes et al., 2004; Perrotta et al., 2005; Vasconcelos et al., 2011; Velasco et al., 2011; Jurado-Ruzafa et al., 2017). The majority of studies describing sex-specific length-at-age (Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996; Kiparissis et al., 2000; Perrotta et al., 2005; Bayhan 2007; Vasconcelos et al., 2011; Velasco et al., 2011) and weight-at-length (Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996; Kiparissis et al., 2000; Santos et al., 2002; Bayhan 2007; Vasconcelos et al., 2011; Velasco et al., 2011) relationships do not report significant differences between sexes, with few exceptions. Differences in sex-specific mean growth parameter estimates for the length-at-age relationship were reported in the Adriatic Sea, however it was not reported whether these differences were statistically significant (Čikeš Keč and Zorica, 2012). Jurado-Ruzafa (2017) reported statistically significant differences between sex-specific mean weight-at-length parameters for Atlantic chub mackerel caught off the coast of Northwest Africa.

Table 2

The objectives of this work are to describe the age and growth characteristics of Atlantic chub mackerel from the coastal Mid-Atlantic and New England region of the United States. We evaluated age estimates from both whole and sectioned otoliths to determine which method results in the greatest precision of age assignment. Otolith-derived age estimates were then used to determine the length-at-age relationship using a suite of non-linear growth models. The weight-at-length relationship was modeled using a power function. Median growth parameter estimates of Atlantic chub mackerel from the Northwest Atlantic were then compared with mean parameter estimates reported from other regions in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Methods

Atlantic chub mackerel were obtained from two commercial fishing enterprises, Lund’s Fisheries Inc. and Seafreeze Limited. Fish were harvested in July through September 2016 (n = 318) and in June, July, and October 2017 (n = 126), using a bottom trawl (Table 1). Additional fish were collected in September 2016 by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Northeast Groundfish Survey (n = 16) in the Northwest Atlantic region (Table 1). All samples were frozen at time of collection. Measurements for total length (TL, mm), fork length (FL, mm), and wet body weight (g) were recorded, and paired sagittal otoliths were extracted from each fish by making a transverse cut to expose the brain cavity. To extend the range of length for determination of growth dynamics, body lengths (BL, mm) of larval fish (n = 60) collected from SEAMAP plankton surveys in the Northern Gulf of Mexico during the month of January were included in the analysis.

The precision of the age estimates between two readers was evaluated using percent agreement (PA) for each structure (sectioned vs. whole). Pairs of otoliths from 50 randomly selected fish (ranging in size from 26.4 cm TL to 38.4 cm TL) were used. Left otoliths were embedded in molds using Epoxicure resin. A transverse section, approximately 0.3 mm thick, was taken at the core of the otolith using a Buehler IsoMet Slow Speed Saw. The sections were mounted on slides with a coat of Flo-Texx. Right otoliths from each pair were left whole and fixed in trays using Flow-Texx as a mounting medium. Age estimates for whole and sectioned otoliths were assigned by counting fully formed annuli at 2 × to 5 × magnification. Sectioned otoliths were read under transmitted light and whole otoliths under reflected light. PA between readers was calculated for both whole and sectioned otoliths. The structure with the greatest agreement between readers was used for age assignment.

A stratified sampling plan was used to subsample otoliths from all size classes and months collected for this analysis. A total of 460 whole otoliths were evaluated by two independent readers with no knowledge of the individual other than catch date. Otoliths that were deformed or damaged were eliminated from the analysis. PA and CV were calculated for between-reader age estimates. After independent age estimates were made for each otolith, readers reevaluated those otoliths where discrepancies existed. If agreement could not be reached, the otolith was omitted from analysis. Otoliths were read blind a second time by the first reader to determine within-reader agreement, to further evaluate the precision of age estimates. Bowker’s test for symmetry was used to evaluate bias of age estimates. All ages were adjusted by date of capture, assuming a birth date of January 1st (ICES, 2015). Ages of one month were assigned to fish captured in January and ranged in length of 2.1 to 7.7 mm BL (Berrien, 1978).

The length-at-age relationship of Atlantic chub mackerel was described using four non-linear models: the two-parameter von Bertalanffy Growth Function (VBGF), three-parameter VBGF, Gompertz growth function, and logistic growth function. These models are commonly used to describe the non-linear dynamics of fish growth (Pardo et al., 2013).

The two-parameter VBGF is:

(L ∞, k, σ p | L i) ∝ Normal (L i | f (L ∞, k, σ p)),

~Normal (L ∞ | 48.21, 0.01),

~Normal (k | 0, 0.0001),

~Uniform (σ p|0, 100),

the three-parameter VBGF:

(L ∞, k, t 0, σ p | L i) ∝ Normal (L i| f (L ∞, k, t 0, σ p)),

~ Normal (L ∞ | 48.21, 0.01),

~ Normal (k | 0.21, 0.01),

~Normal (t 0 | -1.47, 0.01),

~ Uniform (σ p | 0, 100),

the Gompertz growth model:

(L ∞, a, r, σ p | L i) ∝ Normal (L i| f (L ∞, a, r, σ p)),

~ Normal (L ∞ | 48.21, 0.01),

~ Lognormal (a | 0.001, 0.0001),

~ Lognormal (r | 0.001, 0.0001),

~ Uniform (σ p | 0, 100),

the Ricker growth model:

(L ∞, a, b, σ p | L i) ∝ Normal (L i | f (L ∞, a, b, σ p)),

~ Normal (L ∞ | 48.21, 0.01),

~ Normal (a | 0, 0.0001),

~ Normal (b | 0, 0.0001),

~Uniform (σ p | 0, 100),

and the power function:

(a, b, σ p | L i) ∝ Normal (L i | f (a, b, σ p)),

~ Normal (a | 0.0038, 0.0001),

~ Normal (b | 3.34, 0.0001),

~Uniform (σ p | 0, 100).

Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) was used to compare competing non-linear growth models. The model with the lowest DIC value was considered to have the greatest predictive capability and selected as the “best” candidate model (Oravecz and Muth, 2017). The median and 95% credible intervals (CI) were calculated from the posterior distributions for each of the parameter estimates of the three-parameter VBGF and the weight-at-length model. Differences in predicted growth were also compared by predicting lengths at each age using estimated mean parameter estimates.

An age-length key (ALK) was computed using FSA and FSAdata packages in R. The ALK was used to identify age composition for the entire sample, by assigning age estimates to individuals based on length measurements. Length class intervals were fixed at 10 cm TL and contingency tables were used to plot the frequency (%) of individuals of a certain age in each length class.

Results

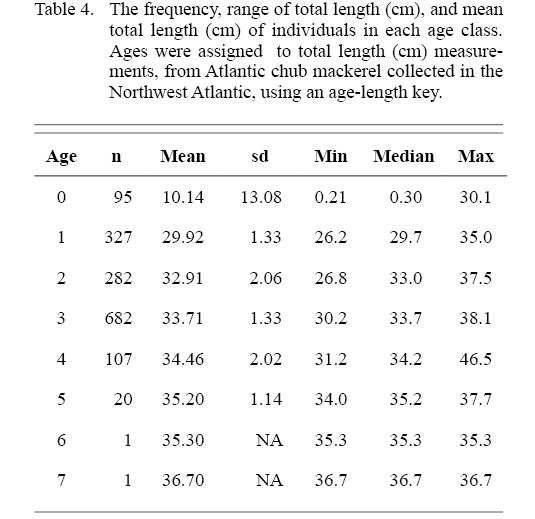

Whole otoliths provided the most precise method for age determination of Atlantic chub mackerel. Age estimates of whole otoliths yielded 72% PA and sectioned otoliths 64% PA. Of the subsample of 460 whole otoliths evaluated in this study 21 were eliminated due to poor quality. Between-reader PA was 66% with a total CV of 19%. Within-reader estimates had a 56% PA and a CV of 24%. After the readers analyzed each otolith independently, otoliths with disagreements were reevaluated in a collaborative manner. A final agreement was reached for 422 otoliths and the remaining 17 otoliths for which an agreement could not be reached were omitted. Assigned age estimates ranged from zero to seven years, from individuals 17.7 to 39.7 cm TL. There was no evidence of systematic disagreement between readers (Bowker’s test of symmetry χ2= 23.51, d.f. = 16, P = 0.10), indicating there was no significant age-specific bias.

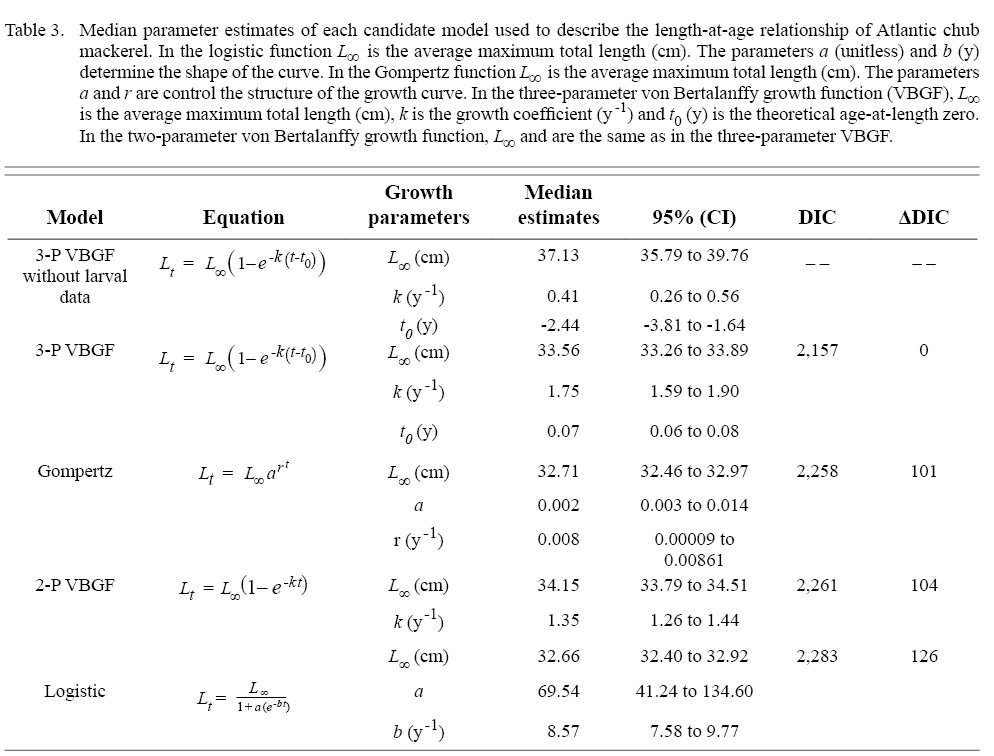

Table 3

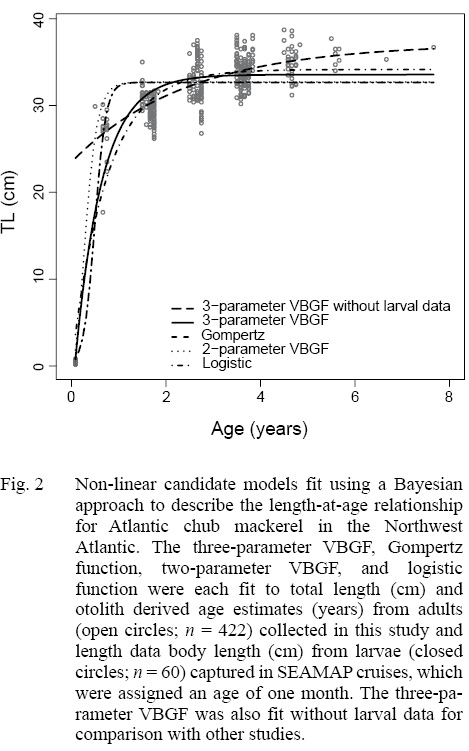

Of the four non-linear candidate models used to describe the length-at-age relationship of Atlantic chub mackerel in the Northwest Atlantic, the three-parameter VBGF had the greatest support (Table 3). The Gompertz function had the next smallest DIC value followed by the two-parameter VBGF, and finally the logistic function. All models predict that Atlantic chub mackerel exhibit rapid growth from age zero to age one and reach asymptotic length around age two (Fig. 2). For comparison with other studies, the three-parameter VBGF was also fit without the inclusion of larval data (Table 1).

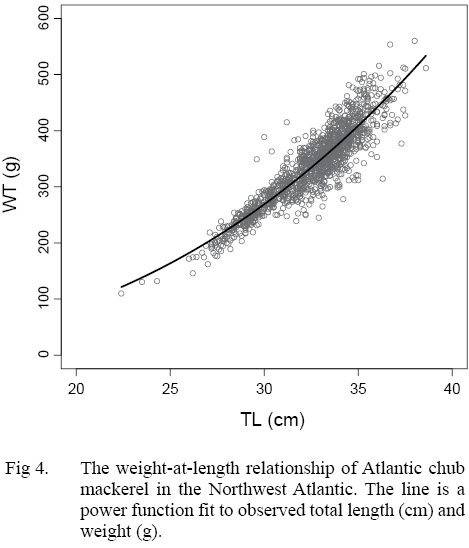

The growth of S. colias in the Northwest Atlantic was evaluated by describing the length-at-age (Fig. 2) and weight-at-length relationships (Fig. 4) and then compared to growth parameter estimates reported in other regions. The mean parameter estimates reported from ten previous studies that described the length-at-age relationship of Atlantic chub mackerel, all fell outside the 95% CI of this study when larval data was used to fit the three-parameter VBGF, indicating significant differences in growth (Table 1). However, when larval data was not included estimates of k (y-1) in four other studies fell within the 95% CI. The estimate of L ∞ from one study in the Mediterranean (Perrotta et al. 2005) and estimate of to (y) from one study in the Northeast Atlantic (Martins, 1996) fell within the 95% CI of the median parameter estimates reported in this study. This study had the highest k (y-1) and the lowest L ∞ (cm) parameter estimates when compared to published parameter estimates. All mean parameter estimates from previous studies used to describe the weight-at-length relationship were significantly different, falling outside the 95% CI of the median parameter estimates from this study (Table 2). The b parameter estimate for this study is smaller than other studies.

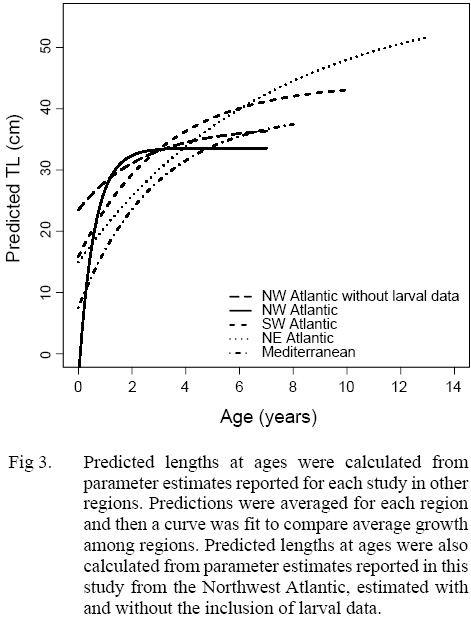

Predicted length-at-age zero was much smaller in the Northwest Atlantic than in other regions when larval data was included and much larger when it was not (Fig 3). When lengths were predicted using mean parameter estimates from the three-parameter VBGF fit with the inclusion of larval data, predicted lengths were greatest in the Northwest Atlantic region at ages one, two, and three (Fig 3). The rate of growth in the Northwest Atlantic slows down after age two and the predicted lengths become more similar at ages three and four, after which predicted lengths in other regions greatly exceeded those in the Northwest Atlantic. When lengths were predicted using parameter estimates from models fit without larval data the predictions were more similar to those in other regions, particularly the Mediterranean. Regions where individuals were captured at greater lengths, also had older fish, and did not reach asymptotic growth as quickly (Fig 3).

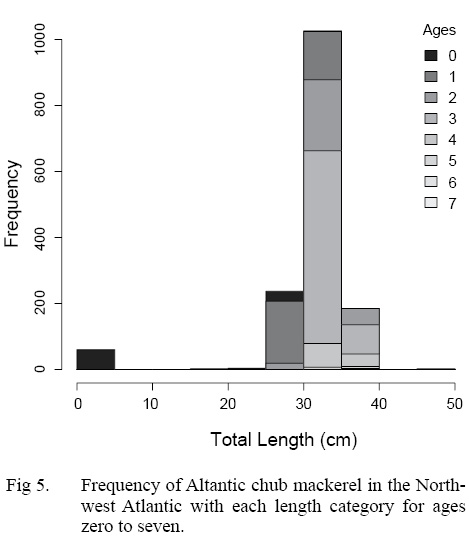

The ALK was used to determine the distribution of ages across length classes of all individuals sampled (Table 4). The majority of individuals sampled were estimated to be age three falling in the 20 to 40 cm TL size class. Overlap of ages in each length class is particularly apparent in the 20 to 40 cm TL size class, where the majority of individuals were sampled (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Table 4

Efforts to assess fish stocks require accurate estimates of ontogenetic growth and these characteristics of Atlantic chub mackerel in the Northwest Atlantic, have not been described. In this study we used Bayesian statistical methods to estimate mean growth model estimates of length-at-age and weight-at-length. In addition to describing the growth for S. colias in the Northwest Atlantic, we found that whole otoliths are the best method for evaluating Atlantic chub mackerel otoliths, that the three-parameter VBGF is the best model to describe the length-at-age relationship, and that growth parameter estimates from this study are significantly different from those reported in the literature from other regions.

Fig. 5

An evaluation of ageing methodology was required because a standardized protocol had not been reported for age determination of Atlantic chub mackerel in the Northwest Atlantic. The reproducibility of repeated age estimates (Campana, 2001), was the main criterion we used to determine which structure should be used (whole or sectioned otoliths) for age estimation. Age determination from whole otoliths had a greater PA and provided increased efficiency in processing relative to sectioned otoliths. The continuation of the use of whole otoliths, the primary ageing structure in other studies on Atlantic chub mackerel growth dynamics, provides the additional benefit of maintaining consistency in methodology among studies.

The precision of age assignment was evaluated using PA and CV. PA between readers was 64%, which is comparable to the PA for all readers reported in the 2015 ICES report of the Workshop on Age Reading of chub mackerel (WKARCM) of 57%. The total CV of age estimates in this study was 20%. In a review of 117 age and growth studies, Campana and Thorrold (2001) suggests that 5% CV or lower be used as a target for fishes that exhibit moderate longevity and ease of otolith readability. The CV attained in this study is much higher than this suggested target, but is an improvement to the 30% CV reported from the 2015 WKARCM (ICES, 2015). Readers in this study experienced difficulty in interpreting otoliths due to false marks or “checks”, which has also been reported in other ageing studies on Atlantic chub mackerel (Vasconcelos et al., 2011; ICES, 2015; Jurado-Ruzafa et al., 2017) and results in inconsistent age estimates. Inconsistency in age estimates are a source of observation error and manifest in biases in the estimation of growth model parameters.

We recommend the three-parameter VBGF be used to describe the length-at-age relationship of S. colias in the Northwest Atlantic. Of the four non-linear models evaluated using objective criteria to reduce errors of model misspecification (Burnham and Anderson, 2004), the three-parameter VBGF was selected as the “best” candidate model. The multi-model approach has been widely used to evaluate candidate length-at-age models (Cope and Punt, 2007; Thorson and Simpfendorfer, 2009; Pardo et al., 2013; Dippold et al., 2016). Previous studies on Atlantic chub mackerel have primarily used the three-parameter VBGF to model the length-at-age relationship (Carvalho et al., 2002; Velasco et al., 2011). Continued use of this model here, and in the future, will serve to maintain consistency in regional comparison of the growth of S. colias.

An ALK was also used to address the potential for bias resulting from a length stratified sampling plan. This arises as a result of fish at a given age potentially straddling several length classes. An ALK provides an estimate of the proportion of individuals in each length class at a given age, rather than an estimate of age. As Morgan and Hoenig (1997) show this must be taken into consideration when using the length-at-age relationship to estimate maturity-at-age. Using the age-length key resolves this issue by explicitly assigning ages to all individuals sampled (Isermann and Knight, 2005).

The description of the length-at-age relationship in this study suggests that individuals in the Northwest Atlantic grow faster and reach a smaller asymptotic length than in other regions. We note that differences in mean growth model parameter estimates have multiple sources of uncertainty and though we primarily focus this analysis on differences in regional growth dynamics, bias can arise from sampling (Goodyear, 1995) and methods of age determination. Spatial and temporal differences among regions exhibit variability in temperature and productivity, which may be responsible for differences in growth. Although temperature has been reported to impact growth, Perrotta et al. (2005) suggests that quality and availability of food has a greater effect on growth of Atlantic chub mackerel. Selectivity likely contributed to differences in reported growth estimates as well. There are a very limited number of commercial vessels in the United States that are capable of capturing Atlantic chub mackerel. It is possible that larger fish are present in the region but are able to swim at speeds that allow them to evade capture. Together, regional patterns of selectivity and availability lead to contrasts in the length and age ranges of fish among studies and it is likely that the narrow length range of adult fish in this study is a result of gear selectivity. The range of lengths was extended in this study by including larval fish captured in ichthyoplankton tows. These smaller individuals ranged from 2.1 to 7.7 mm BL. Without the inclusion of smaller individuals, the three-parameter VBGF predicted length-at-age zero to be 23.5 cm TL. Berrien (1978) reported the size at hatching to average 0.31 cm SL, making the predicted length-at-age zero unrealistically large. Although the inclusion of larval data provides a biologically realistic description of growth in the Northwest Atlantic, other studies on Atlantic chub mackerel have not included these data.

The range in mean weight-at-length parameter estimates among regions indicates the existence of geographic variation. The scaling exponent b estimated in this work is smaller than reported estimates in all previous studies. This suggests that weight-at-length is depressed in the Northwest Atlantic, relative to that exhibited in other regions. Some of the observed contrast may be due to sampling error, individuals were collected during different months and years in each study, which are likely to vary in temperature and productivity. These factors impact growth and condition of fish (Martin, 1949; Houde, 1974; Powell et al., 2004; Martins, 2007) and lower b values have been reported during the colder parts of the year (Čikeš Keč and Zorica, 2012). Some regions, such as the Canary Islands, exhibit seasonal fluctuations in weight-at-age of Atlantic chub mackerel (Lorenzo and Pajuelo, 1996) with the greatest values from March to September and reductions in October to February.

A small number of studies in other regions have validated annuli formation of Atlantic chub mackerel. Vasconcelos, et al. (2011) reported that one translucent and one opaque band were deposited each year for Atlantic chub mackerel collected off Madeira Island and used marginal increment analysis to validate annuli formation for individuals aged zero to four years. We were unable to collect samples throughout the year in this study to conduct marginal increment analysis due to the absence of fishery-dependent and fishery-independent catch in the Northwest Atlantic. Mark-recapture studies are another method recommended for validating age estimates, because it allows the true age of the fish to be determined (Campana, 2001). This type of study could be applied in the future but requires extensive resources.

The research presented here provides a description of Atlantic chub mackerel growth in the Northwest Atlantic. Description of length-at-age allows the development of age-length keys and an understanding of the age-composition of harvest in the commercial fishery. This information can be implemented into age-structured models and allow reconstruction of population dynamics which is the primary assessment method used in fisheries science (Cope and Punt, 2007). The weight-at-length relationship is useful for transforming observed length measurements into weight in order to calculate estimated biomass and for comparing the relative condition of the fish (Froese, 2006). The information reported in this study will greatly improve understanding of Atlantic chub mackerel life history and directly inform the future management of the Northwest Atlantic stock.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation Industry/University Cooperative Research Center SCeMFiS (Science Center for Marine Fisheries) through membership fees under the direction of the Industry Advisory Board (IAB). SCeMFiS administrative support is provided by NSF award #1266057. Conclusions and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors. We thank J. Kaelin at Lund’s Fisheries Inc., and M. Lapp at Seafreeze Limited. We thank S.J. Sutherland and E. Robillard from NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center. Thank you to E. Powell (The University of Southern Mississippi) for providing invaluable feedback on this work and E. Bochenek (Rutgers University) for assisting with the collection of biological samples.

References

Ballagh, A. C., D. Welch, A. J. Williams, A. Mapleston, A. Tobin, and N. Marton. 2011. Integrating methods for determining length-at-age to improve growth estimates for two large scombrids. Fishery Bulletin, 109(1): 90–100.

Bayhan, B. 2007. Growth characteristics of the chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus Houttuyn, 1782) in Izmir Bay (Aegean Sea, Turkiye). Journal of Animal Veterinary Advances, 6(5): 627–634.

Berrien, P. L. 1978. Eggs and larvae of Scomber scombrus and Scomber japonicus in continental shelf waters between Massachusetts and Florida. Fishery Bulletin, 76(1): 95–115.

Bertalanffy, L. Von. 1938. A quantitative theory of organic growth (inquiries on growth laws. II). Human Biology, 10(2): 181–213.

Burnham, K. P., and D. R. Anderson. 2004. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research, 33(2): 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644

Campana, S. E. 2001. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. Journal of Fish Biology, 59(2): 197–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2001.tb00127.x

Campana, S. E., and S. R. Thorrold. 2001. Otoliths, increments, and elements: keys to a comprehensive understanding of fish populations? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 58(1): 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1139/f00-177

Carvalho, N., R. R. G. Perrotta, and E. Isidro. 2002. Age, growth and maturity in chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus Houttuyn, 1782) from the Azores. Life and Marine Sciences 19A: 93–99.

Catanese, G., M. Manchado, and C. Infante. 2010. Evolutionary relatedness of mackerels of the genus Scomber based on complete mitochondrial genomes: Strong support to the recognition of Atlantic Scomber colias and Pacific Scomber japonicus as distinct species. Gene 452(1): 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2009.12.004

Čikeš Keč, V., and B. Zorica. 2012. Length–weight relationship, age, growth and mortality of Atlantic chub mackerel Scomber colias in the Adriatic Sea. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 93(2): 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315412000161

Cope, J. M., and A. E. Punt. 2007. Admitting ageing error when fitting growth curves: an example using the von Bertalanffy growth function with random effects. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 64: 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1139/f06-179; https://doi.org/10.1139/f07-095

Dippold, D. A., R. T. Leaf, J. R. Hendon, and J. S. Franks. 2016. Estimation of the length-at-age relationship of Mississippi’s Spotted Seatrout. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 145(2): 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028487.2015.1121926

Froese, R. 2006. Cube law, condition factor and weight–length relationships: history, meta-analysis and recommendations. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 22: 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.2006.00805.x

Gompertz, B. 1825. On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 115: 513–583. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1825.0026

Goodyear, C. P. 1995. Mean size at age: An evaluation of sampling strategies with simulated Red Grouper data. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 124(1993): 746–755.

Hernández, J. J. C., and A. T. S. Ortega. 2000. Synopsis of biological data on the chub mackerel: Scomber japonicus Houttuyn, 1782. FAO Fisheries Synopsis.

Houde, E. D. 1974. Effects of temperature and delayed feeding on growth and survival of larvae of three species of subtropical marine fishes. Marine Biology, 26(3): 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00389257

ICES. 2015. Report of the Workshop on Age Reading of chub mackerel (Scomber colias) (WARCM). Lisbon, Portugal.

Isermann, D. A., and C. T. Knight. 2005. A computer program for age–length keys incorporating age assignment to individual fish. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 25(3): 1153–1160. https://doi.org/10.1577/M04-130.1

Jurado-Ruzafa, A., E. Hernández, and T. G. Santamaría. 2017. Age, growth and natural mortality of Atlantic chub mackerel Scomber colias Gmelin 1789 (Perciformes: Scombridae), from Mauritania (NW Africa). VIERAEA. 45: 53–64.

Kiparissis, S., G. Tserpes, and N. Tsimenidis. 2000. Aspects on the demography of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus Houttuyn, 1782) in the Hellenic Seas. Belgian Journal of Zoology, 130(1): 3–7.

Lorenzo, J. M., and J. G. Pajuelo. 1996. Growth and reproductive biology of chub mackerel Scomber japonicus off the Canary Islands. South African Journal of Marine Science, 17(1): 275–280. https://doi.org/10.2989/025776196784158635

Martin, W. R. 1949. The mechanics of environmental control of body form in fishes. The Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory 70(58): 1–91.

Martins, M. M. 1996. New biological data on growth and maturity of Spanish Mackerel (Scomber japonicus) off the Portuguese coast (ICES Division IX a). International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Lisboa, Portugal.

2007. Growth variability in Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) and Spanish mackerel (Scomber japonicus) off Portugal. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64: 1785–1790. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsm163

Mendes, B., P. Fonseca, and A. Campos. 2004. Weight-length relationships for 46 fish species of the Portuguese west coast. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 20(5): 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.2004.00559.x

NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service). 2019. Annual commercial landings statistics. https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/commercial-fisheries/commercial-landings/annual-landings/index.

Morgan, J., and J. Hoenig. 1997. Estimating maturity-at-age from length stratified sampling. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 21: 51–63. https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v21.a4

Moutopoulos, D. K., and K. I. Stergiou. 2002. Length-weight and length-length relationships of fish species from the Aegean Sea (Greece). Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 18: 200–203. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0426.2002.00281.x

Oravecz, Z., and C. Muth. 2017. Fitting growth curve models in the Bayesian framework. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1): 1–21.

Pardo, S. A., A. B. Cooper, and N. K. Dulvy. 2013. Avoiding fishy growth curves. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12020

Perrotta, R. G., N. Carvalho, and E. Isidro. 2005. Comparative study on growth of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus Houttuyn, 1782) from three different regions: NW Mediterranean, NE and SW Atlantic*. Revista de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero, 17: 67–79.

Plummer, M. 2016. rjags: Bayesian Graphical Models using MCMC.

Powell, A. B., R. T. Cheshire, E. H. Laban, J. Colvocoresses, P. O’Donnell, and M. Davidian. 2004. Growth, mortality, and hatchdate distributions of larval and juvenile spotted seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus) in Florida Bay, Everglades National Park. Fishery Bulletin 102(1): 142–155.

R Core Team. 2015. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.

Ricker, W. E. 1975. Computation and interpretation of biological statistics of fish populations. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 191: 1–382.

Santos, M. N., M. B. Gaspar, P. Vasconcelos, and C. C. Monteiro. 2002. Weight–length relationships for 50 selected fish species of the Algarve coast (southern Portugal). Fisheries Research, 59: 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00401-5

Sinovčić, G., M. Franičević, B. Zorica, and V. Čikeš-Keč. 2004. Length-weight and length-length relationships for 10 pelagic fish species from the Adriatic Sea (Croatia). Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 20(2): 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0426.2003.00519.x

Thorson, J. T., and C. A. Simpfendorfer. 2009. Gear selectivity and sample size effects on growth curve selection in shark age and growth studies. Fisheries Research, 98: 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2009.03.016

Vasconcelos, J., M. A. Dias, and G. Faria. 2011. Age and growth of the Atlantic chub mackerel Scomber colias Gmelin, 1789 off Madeira Island. Life and Marine Sciences, 28: 27–70.

Velasco, E. M., J. Del Arbol, J. Baro, and I. Sobrino. 2011. Age and growth of the Spanish chub mackerel Scomber colias off southern Spain: a comparison between samples from the NE Atlantic and the SW Mediterranean. Revista de biología marina y oceanografía, 46(1): 27–34. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572011000100004

: Daley, T.T. and R.T. Leaf. 2019. Age and growth of Atlantic chub mackerel (

) in the Northwest Atlantic.

: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v50.m717